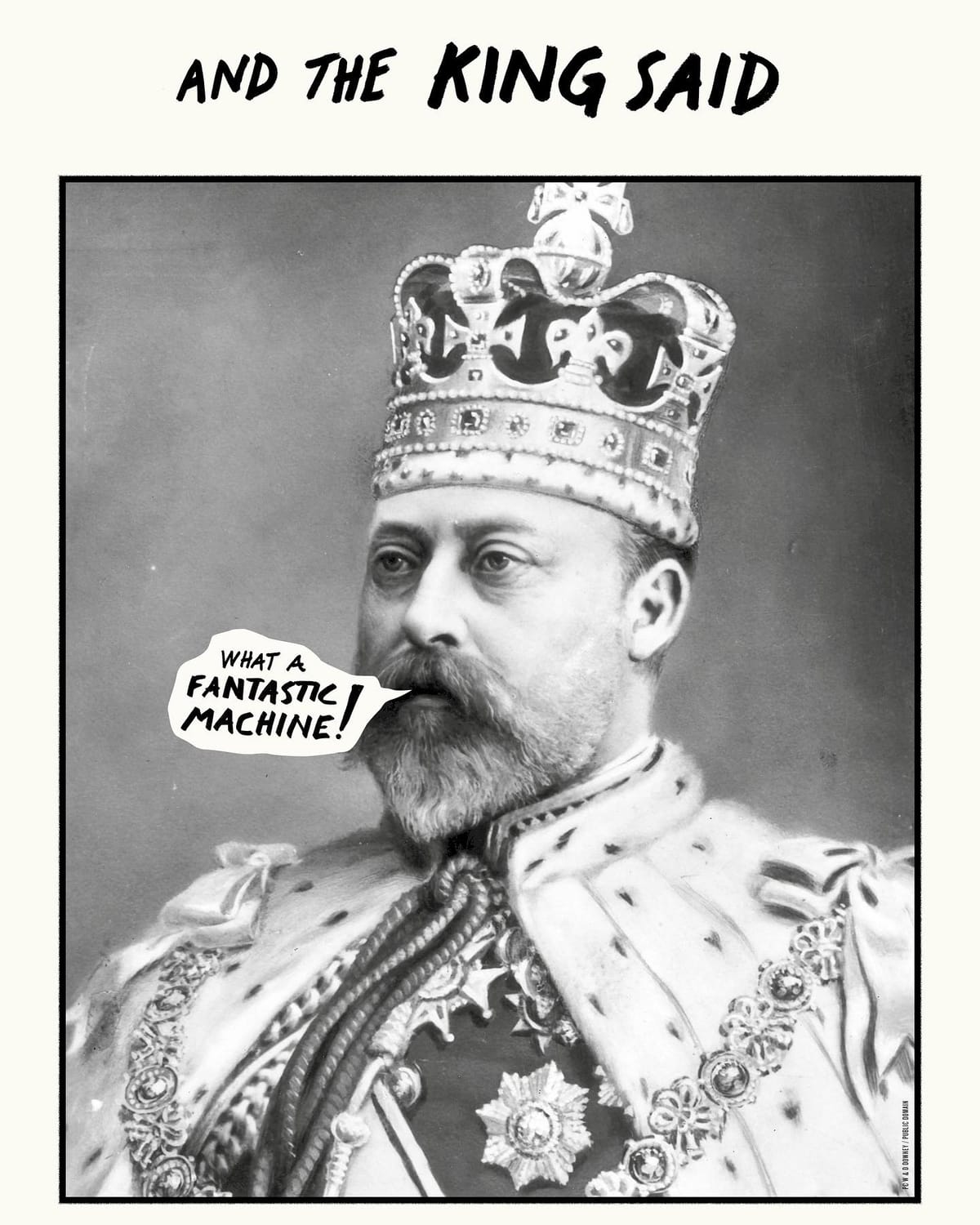

And the King Said, What A Fantastic Machine

Early on in Axel Danielson & Maximilien Van Aertryck's essay film, we're told the story of George Méliès' The Coronation of Edward VII. The same year in which he'd complete A Trip to the Moon, Méliès was hired to film a "pre-enactment" of the upcoming coronation of the British king. Despite being released to coincide with the actual event, there was no pretense that it was a recording of the actual coronation. Nonetheless, we're informed that when Edward VII was shown the film, he remarked "What a fantastic machine the camera is!"

On its face, this comment is very apt, presenting the dichotomy of film. It's a tool used to capture and to deceive, to deconstruct power as well as cement or even gather it. Our relationship to the camera is examined, how it impacts our self-perception, our self-esteem, and our interactions with the world. As is the camera's role as dispassionate, objective observer, and how we forget the same does not necessarily extend to the image's subject.

Making it feel all the more poignant that I cannot find the source of the titular quote. It only appears in materials relating to the film itself, and is nonexistent online before December 2022, when it was announced as part of Sundance 2023. Danielson & Van Aertryck are mimicking the very technique on which they're musing in order to illustrate their point, that information spread via screen is more readily accepted as fact with limited attempts made to verify. It's a fact constantly exploited by ideologues and authoritarians, driven home by the collage of clips which follows depicting world leaders waving to their constituents whilst accompanied by a military procession.

The remaining seventy-five minutes muse on the various ways this manipulation is made manifest, and the impacts it has on our perception of the world. We weave through related subjects, touching on the framing of photographs, the commercialization of news programs through the advertising-fueled business model of television, and the way the idealized images of others drive our own behavior in the never-ending pursuit of attention online. Each section consists of some bits of narration, and a series of videos which exemplify it. They flow naturally from one to the other, like a friend is taking you on a journey through their train of thought.

The downside of this wide ranging collection of ideas is no one topic gets explored in much depth. They're all well demonstrated, but there are few insights which would be foreign to the average digital native. The most interesting is the framing of harassing and swatting a lifestreamer as a form of viewer creation, while simultaneously using great editing to really make us feel the terror Paul Denino (aka Ice Poseidon) experiences at their hands. And it is effective, but it lasts less than five minutes before shifting back to the overall point of our consumption of reality through our screens. The filmmakers don't espouse a ton of extra thoughts on their examples, mostly telling us a piece of history or some cultural occurrence, and trying to let the juxtaposition of images speak for themselves. Which is effective, but only to a point. The core point is made in the opening minutes through a fifteen second video of a woman wordlessly demonstrating the incredible simplicity of misleading viewers without any effects or edits or camera tricks. While that aspect is expanded upon, and the movie can't be reduced to that one clip, the investigation promised by it never materializes.

The film contains strong shades of Theo Anthony's recent All Light, Everywhere, but lacks its focus. Anthony anchored his arguments and explorations to the surveillance state, using its own devices and a metanarrative structure to peel back the curtain and deconstruct its (and, by extension, our) key assumptions about the function of the camera. Which helps to put into sharp relief a truism about movies: limitations are helpful. Even when discussing an expansive subject, having some box to push and strain against helps to get your point across, as we think we know the boundaries until we see you struggle against or even break them, yielding new perspectives. As is, this movie tries to take the shape of its nonexistent container, resulting in some neat imagery, some useful ideas, but ultimately diffusing too much to have any staying power.