Asteroid City

Anderson becomes self-aware, to great effect

Wes Anderson has long been taken with narrative nesting, as many of his movies utilize various forms of the device, especially frame tales. He first deployed it in The Royal Tenenbaums, which was presented as being narrated from a book checked out from the library, complete with chapter headings. By The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson was going four levels deep (a girl opens a book recalling a meeting recounting a memory). Most recently, The French Dispatch was composed of short stories printed in the magazine on the occasion of the death of their editor, most of which are themselves tales of someone recounting some event.

So it should come as no surprise that something similar is true of Asteroid City. However, whereas in previous works it served to distance the viewer from the story, and allow clarifications or fast forwards from an omniscient narrator, here it is an inextricable piece of the story Anderson wishes to convey. Instead of surrounding the narrative, it plays off of and interacts with the story and characters, both informing and being informed by them. Everyone is very consciously an actor, which leads to a very odd atmosphere, even for an Anderson film.

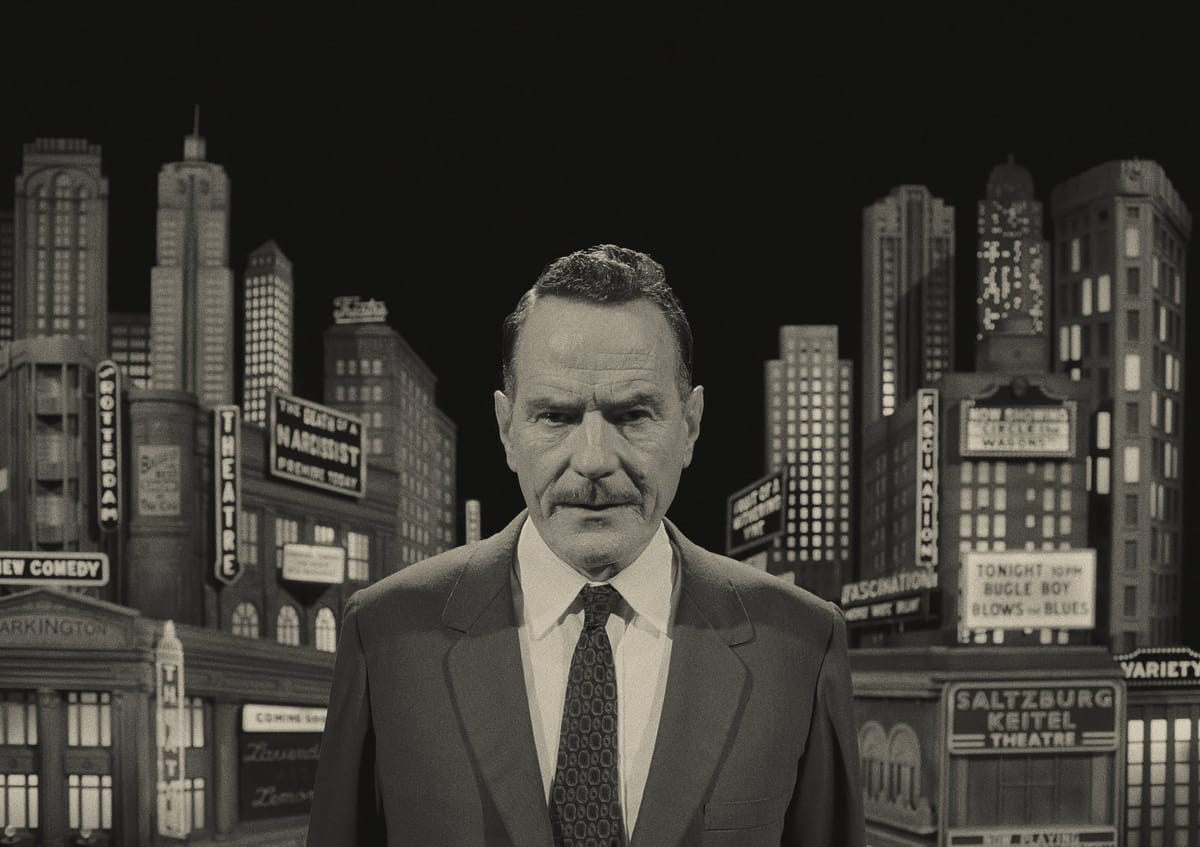

As explained by The Host (Bryan Cranston), Asteroid City is not a play, nor does it depict real events, nor is it a real place. Rather, this fictional stage production is a device for their television program to illustrate the process of creating such a work. As such, we jump back to the “real world” often for dramatizations of various vignettes along the way to creating the play. The writer (Conrad Earp, played by Edward Norton) struggles to nail down characters. The director (Schubert Green, played by Adrien Brody) lives on the set for two years. And so on. In this way, it seeks to pull back the curtain on itself, and attempts to use the deliberate fabrication of reality as a deeper window into it.

To many, this will be a frustrating movie. The layers of artifice draped in Anderson’s trademark pastels and somewhat fantastical setting and events make for a surreal, disorienting experience. The play is in color, while the television program is (mostly) in black and white. There are unexplained happenings, strange speech patterns, bleeps and bloops which “stay the same” despite constantly changing (although they do cycle), and occasionally a roadrunner puppet which says “meep meep”. On its surface, this is a picture which is almost entirely style, along with a bunch of outstanding performances and exquisite scenes. The absurdity lends itself well to a ton of low-key hilarious interactions and lines; you’re unlikely to bust a gut, but you’ll constantly be chuckling.

But almost everything about the film is screaming at you that there’s more to it than that. Anderson is such a deliberate and careful filmmaker that anything seemingly out of place feels like it’s there for a reason, even if I haven’t yet clocked what it is. For example, that roadrunner strikes me as a representation of the arbitrary conveniences of a fictional story, owing to a throwaway line early on in which we learn the bus ran over a coyote, leaving him without a natural predator. In this place, things happen because they need to happen, allowing the story to convey a larger idea. Similarly, the nuclear tests and car chase, normally exciting events which could be the catalyst for their own film (one of which releases in a few weeks), are uninteresting background as the people have blinders on to events which don’t concern them.

Foreshadowing occupies a strange space in a movie such as this. There’s room for two flavors. Conversations in the play which foretell future events, such as when J.J. (Liev Schreiber), Sandy (Hope Davis), and Roger (Stephen Park) are discussing the probability of alien life a short while before the alien shows up. It also comes from the real world, when the cast refers to aspects of the play or quotes from it which we haven’t gotten to yet, such as Jones Hall’s (Jason Schwartzman) monologue when angling to land the role of Augie Steenbeck. However, there’s a third angle which is only possible in this type of construction: the foreshadowing which instead reveals how the play has changed. Characters in the real world saying things which are clearly framed as part of the play, and yet never show up. The most prominent example is when Polly (Hong Chau) suggests to Schubert that Mercedes Ford (Scarlett Johansson) as Midge should try saying her act three line “Maybe we are doomed” after the door closes. Yet when the line eventually comes, itself slightly altered, there’s no interaction with the door, just staring out of a window. Why? Because the play has changed such that it’s no longer relevant.

I could go on talking about nice flourishes like this, but their details aren’t important, even if they’re enjoyable. Their existence only matters insofar as they serve a larger purpose. And while I don’t quite think it brings everything together, he clearly has overarching themes in mind.

Although it’s blatantly stated, I think the refrain of “You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep” is the key to Anderson’s thought here. That is, deception is necessary to get at a deeper truth. The experience of having the foundation of your life shaken can only happen if you’ve been deceived first, such as Augie lying to his kids about whether their mother is alive. This leads to its corollary: that if you’re too clear eyed, you’re not open minded enough to allow yourself to be shown more complex, less obvious ideas. Which slides together nicely with all the investigation of storytelling that he’s doing. When you buy into a narrative, you’re allowing it the possibility of teaching you something more. The spell would be broken if you were focused on identifying every mistake. Stories of all types require some amount of suspension of disbelief to work their magic.

There are so many details big and small this applies to. How quickly Augie accepts the nearby nuclear tests. The speed with which everyone adjusts to the idea that we’re not alone. The thought that maybe they’re doomed can only follow from first accepting that they did indeed witness an alien and not some trick. It even works if we step out of the play: Conrad Earp (Edward Norton) has to allow himself to be won over by the audition of someone in whom he’s not interested in order to find a lover. Jones has to trust Schubert’s insistence that he’s playing Augie right despite not truly understanding him. And on and on. A lot of these scenes are played as jokes, and they land well as such; Anderson did not forget to make a fun movie. But they also act as a smokescreen, distracting you from their resonance with that central idea.

This idea dovetails nicely with the line between fiction and reality, which he’s constantly playing with. The Host accidentally appears in a scene, and at one point Jones steps off stage to address Schubert. The whole time, Anderson wants us to feel like not only is it a play, but it’s one under development. The speech patterns mentioned earlier often strike as actors trying to feel out their character’s voice, and doing so clumsily.

All that being said, while it’s all there to be discovered, most of them don’t land emotionally. The movie’s opacity keeps us at a distance, meaning even when it’s ideas poke through, it’s hard for them to have an emotional impact. This is a very cold movie, moreso than most of his films, which have nakedly been about humanity. Caricatures, sure, but people in all their messy lives. Here, everyone and everything feel like props, meaning that despite your laughter and wonder, you will not cry.

Stepping away from the themes, what of the cast? It’s his usual absolutely bonkers ensemble, and everyone is doing an excellent job. But I’ve gotta call out Jeffrey Wright, who absolutely kills it in his few scenes as General Grif Gibson. His personal speech when we first meet him is incredible; I will never look at the phrase “But that was life” the same way again.

Asteroid City is a hard movie to talk about. It’s opaque, it’s meta, and it has few comparisons. It’s funny, but without allowing you to get close to the characters. It has things on its mind, but it doesn’t give them up without a fight. To me, it represents the apex of Anderson’s narrative sophistication. He’s found another gear, another level of mastery. Unfortunately, in doing so, he lost some of the charm and cohesion that make Grand Budapest Hotel and The Royal Tenenbaums such wonderful and poignant films. Which leaves it as a very good movie, but only the mid-tier of his filmography. That being said, its advances give me incredible hope for his future. One has to imagine he’ll figure out how to marry the structural precision here with the humanity in his top-tier, and then we’ll be in for quite a treat.

In conclusion, I highly recommend it for Wes Anderson fans. But I caution those who are mere Anderson-curious: while it has plenty of stand-alone moments, it’s not a good gateway into his world. For that, maybe try Moonrise Kingdom; that was my first, and I was so taken with and fascinated by it that six weeks later, I’d seen every feature he’d made. After that, come back to Asteroid City, and it will yield you much fruit.